Sometimes we are our own worst enemy.

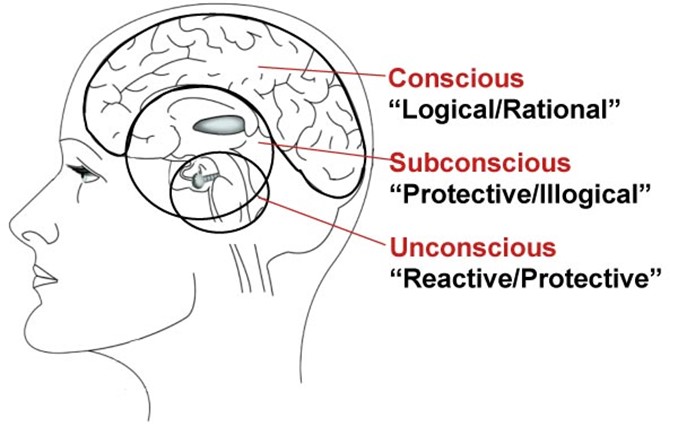

The way our brain processes and perceives incoming information can be a major obstacle. There are three distinct parts of our brain that play a big role in every conversation that you want to hold: the unconscious, subconscious, and conscious brains.

What is a difficult conversation?

Any conversation that you would avoid at all costs qualifies as a difficult conversation. Sometimes our fears in holding such conversations are based on our past experience—real or perceived. Sometimes we know that the topic is sensitive and there is the real possibility of it going awry. At other times the conversations that we avoid are with those people whom we know always react emotionally. So, not knowing the outcome becomes the justification for avoiding the situation altogether.

And on top of all that, our brain doesn’t do us any favors.

The “Unconscious” Brain

This part of your brain is a “reactive protective” mechanism whose sole purpose is to ensure the survival of the species. For example, if you take a jab at a person’s face, they might instinctively blink, jerk back their head, or even attempt to block your hand—all because of an unconscious reaction to protect themselves.

The reactive behavior occurs as a measure of self-protection or preservation. There is no room for conscious reasoning in this process—it takes the brain only milliseconds to assess the situation and send signals to different parts of the body calling for battle stations for self-protection. The process occurs unconsciously—or outside any deliberate or logical processing on your part. It seems to just happen, whether you want it to or not.

So, if emotions just seem to explode onto the scene out of nowhere, you know your subconscious is reacting to the situation. When this happens it takes a fair amount of self-discovery to uncover the thinking that is behind your reaction.

The “Subconscious” Brain

This subconscious part of your brain is a “protective illogical” mechanism. While the unconscious brain protects your physical person, the subconscious works to protect your “non-physical” self—the mental and emotional part of who you are. It focuses on the system of values or the rewards you have assessed, accumulated, or constructed over time through your life experiences.

For example, suppose that every time you have attempted to hold a difficult conversation, the results have been catastrophic… or even just unpredictable. Perhaps the other person became emotional and erupted with dramatic fireworks. Or perhaps they refused to engage, clamming up and avoiding you. If these results have repeated, then your experience forms the basis of your expectations about attempts to talk about difficult topics.

Suppose you need to give feedback to a coworker who is not doing their fair share of the work. At the very suggestion of holding such a conversation, your subconscious brain begins to kick into overdrive and starts providing you the following messages:

“No, no, no—Not a good idea!”

or

“This won’t go well! It has never gone well!”

or

“You don’t know how to do this—You’ll blow it again!”

or

“This is better left alone. Just

The subconscious part of the brain is extremely efficient. It conjures up supporting emotions and excuses to make sure its message is effective, emotions such as anxiety, nervousness, or frustration. These feelings make us uncomfortable, so we conclude that this difficult conversation “doesn’t feel right” or we tell ourselves, “I’m not comfortable talking about this!”

If the subconscious protective-illogical part of your brain is allowed to call the shots, you will either avoid the conversation completely (a “flight” response) or attempt to hold the conversation while in a heightened emotional state (a “fight” response). Many, many people interact with others based on this “fight or flight” mindset. And since this mindset is primarily focused on preserving the self in one way or the other from any perceived attack, there is no room to allow the person to learn from others by exploring different perspectives of tough issues. The subconscious tries to limit the way we interact.

The “Conscious” Brain

The conscious part of your brain functions as a “logical-rational” mechanism. While the unconscious and subconscious parts of your brain are stimulated by events or accumulated past history, the conscious brain is stimulated by words that are formulated into questions. Questions allow us to logically and analytically explore the rationality of our thinking—the thinking that our subconscious would prefer to move us to fight or flight.

Let’s look at the previous scenario again from the perspective of how the conscious part of our brain works. Suppose you recognize that you are feeling uncomfortable about talking to your coworker about his lack of productivity. The little voice in your head is screaming, “This won’t go well!” If you engage your conscious brain instead, you might ask yourself—and answer—the following questions:

“What evidence do I have that the conversation won’t go well?”

“How could I approach this person to be successful?”

“What do I not know about this situation?”

“What do I need to know that I don’t know?”

Asking yourself several questions will engage your conscious, rational brain. You will begin to defuse whatever negative emotions you are feeling, and you will be better able to assess the accuracy and completeness of your thinking.

In other words, you will be better able to recognize where you are missing information and where you might have made assumptions that might just be downright wrong. This will increase your confidence and your ability to create the conversation you want to hold.

Preparing for a difficult conversation by using your conscious brain to determine what happens will literally create a different outcome. If you allow the reactive two-thirds of your brain to manage the conversation, it will be operating from incomplete and invalid assumptions, and you will literally leave the success of the conversation to chance.

How Can You Prepare to Hold Difficult Conversation?

Prepare the conversation successfully by asking yourself questions. The specific questions below will help you evaluate and prepare in the context of your circumstance. We have arranged the questions by topic; you will want to consider all these factors because they will influence your delivery as well as the specific material and data you decide to bring up in the conversation:

|

Purpose: |

“What do I want to change?” “What do I want? Why?” |

|

Person: |

“What do I know about this person?” “What position do they hold?” “How might they respond to this topic?” “What do they want?” |

|

Relationship: |

“What is the current status of our relationship?” “What is our current level of trust?” |

|

Past: |

“What has happened/is happening?” “What assumptions have I made about them?” |

|

Plan: |

“What are we going to do?” “How will we get there?” |

Your answers to these questions will help you organize your thinking about what you want to accomplish in the conversation, how you should best approach the topic with the individual, and what facts you are basing your opinions on.

You simply cannot afford for an important conversation to be “hit or miss.” And if you don’t know what you want as an outcome, you are less likely to achieve it. Preparing the conversation by thinking it through as we have outlined above is the only way to allow the conscious, logical-rational part of your brain to be in the driver’s seat. Anything else is simply too unpredictable and ineffective.

Taking the time to prepare and think through the situation will ensure that your conversation will stay in the logical, rationale realm.